Trending

Stock Options and Other Equity Compensation Strategies

/in Equity & Compensation/by Benjamin - WonderlyShare this entry

When Founders and Executives of Startups Should Consider Financial Wealth Planning

Building a great technology startup and leading it to an exit or IPO is a feat accomplished by a rare few individuals. The journey can also be highly-lucrative, and it’s not uncommon for founders and early executives to find themselves unfamiliar with how to manage their newfound wealth (it’s what many would call a “nice” problem to have.)

But it’s still a challenge. Planning early is the best way to maximize returns and make sure that your money lasts. Meeting with a startup financial advisor at one of these critical junctures can allow you to preserve the wealth that you worked so hard to produce.

We recently spoke with Jeff Schnitz and Andy Pelletier, who respectively lead the wealth advisory and private-banking operations at Silicon Valley Bank. We discussed how founders and executives at #breakawaygrowth companies should think about balancing prudent financial planning with the understandable desire to enjoy the fruits of one’s wealth after an IPO or M&A event.

We recently spoke with Jeff Schnitz and Andy Pelletier, who respectively lead the wealth advisory and private-banking operations at Silicon Valley Bank. We discussed how founders and executives at #breakawaygrowth companies should think about balancing prudent financial planning with the understandable desire to enjoy the fruits of one’s wealth after an IPO or M&A event.

Here are edited excerpts of our conversation:

How should people, who stand to become wealthy, think about financial planning?

Jeff: When you’re engaged with financial planning, you’re thinking about the very long term. When your startup is young but has created some value, you might start thinking through questions like, when your assets are liquid, how are you going to handle it? How will you bucket assets and plan for the next 3, 5, or 10 years?

Is it ever too early to start that conversation?

Andy: If it’s early, it might be a brief conversation. We’ll end by agreeing to check in when there’s a trigger event, such as when your company raises at a 2X valuation from the last round.

We recently met with a CEO who doesn’t have liquid wealth, but he has substantial private value in his company. We were having a quick conversation, not an extensive one, about things he will want to think about in his estate plan and insurance. For now, that will probably be enough for his particular situation. We probably won’t speak again until he’s close to getting married, buying a home, taking some money off the table via a secondary, or engaging in a merger or acquisition.

How do you start helping people think about developing a financial plan?

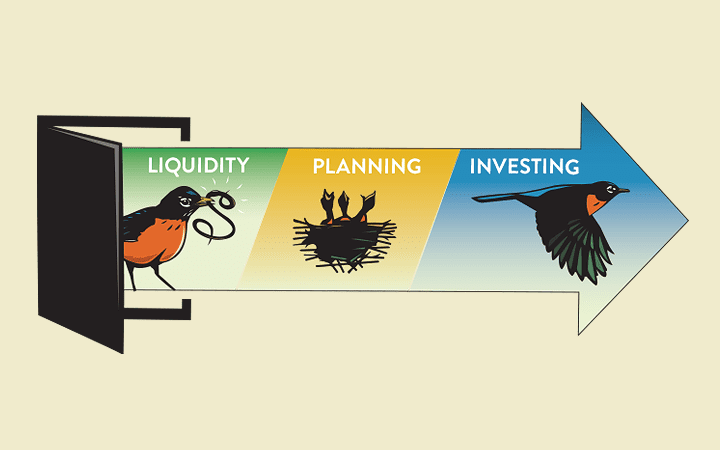

Jeff: A founder should frame in their minds three core constructs—liquidity, planning, investing—each handled sequentially and conjointly.

3 CORE CONSTRUCTS TO FINANCIAL PLANNING

Liquidity is about assessing what assets one has on hand (real estate, cash, bonds, public stock, private stock), forecasting the appropriate selling of those assets, assessing one’s ability to secure various types of loans and to what extent one can handle those liabilities on their personal balance sheet.

Planning is about implementing a household budget and spending forecast, estate planning for securing assets for the spouse and kids, insurance planning to protect those assets and tax planning for the short and long terms.

Investing is about mapping-out major personal and family purchases, cash on hand that is needed for unexpected short-term needs, public market portfolio construction and a reserve for philanthropic wishes.

What is risk planning in the context of financial planning?

Jeff: Risk planning is about looking at one’s longest-range goals and then backing that into today’s decisions. We certainly focus on topics such as insurance and cash flow planning.

Insurance is a key risk mitigant. Pretend we’re talking about a founder of a high-flying startup who may have eight figures’ worth of private stock. Let’s say he backs into somebody who’s riding a bike. The bicyclist sues after googling and learning that this person is part of a unicorn.

Having appropriate umbrella coverage is important for these people. They don’t have the liquid assets to deal with such a suit, but they might end up liable, anyway, through the legal system. It’s also usually relevant to consider life insurance, and directors and officers insurance for the business.

Cash flow planning is also a critical part of managing risk. Let’s say someone wants to send their kids to college or grad school in 7 years or buy a vacation home in 10 years. But, today, they have some cash on hand where they have an opportunity to invest in a friend’s new startup. First, we discern whether they have 3, 5, or 10-year assets to pay for those 7 and 10-year goals (e.g., private stock, promissory note investments, LP structured investments, public market investments). If the answer is no or very little current assets then the possible startup investment could be ill-advised because, if everything works, it will take on average 12 years for an exit to be realized which would miss both the 7 and 10 year goals. Instead, they might be better served to get into a 529 account or a public market fund.

People also perceive risk much differently, and so they’re going to have personal biases. We just want to educate them to make better choices based on their own specific circumstances.

How does getting liquidity on one’s private stock factor into a financial plan?

Jeff: First it starts from a position of assessing one’s confidence. There are two sides to that coin—confidence in one’s financial plan and associated decision-making and confidence in the prospect of one’s company realizing a successful exit. Let’s assume the former is in good shape. The latter has to do with the health of the business metrics (e.g., revenue, growth, margins) and growing valuation. If a prosperous exit is visible to the founder within a one to three-year time horizon, they might consider selling a little of their equity.

To be clear, this wouldn’t be about the founder cashing out. The aim here would be to either fund some aspect of their financial plan or to get all of their shares into long-term capital gains treatment, assuming they hadn’t previously filed their 83(b) election back when they were granted the shares. Getting the desired liquidity could be achieved through a variety of loan or direct sale instruments, assuming management and the board are supportive. Importantly, the vast majority of the founder’s shares would remain illiquid and ride entirely on building a great business and the eventual successful IPO or M&A.

What are some of those scenarios when the planning didn’t happen, and you encounter a bit of a mess?

Andy: If someone’s been holed up eating ramen noodles for the last nine years, and then suddenly on paper, they’re worth a lot of money, we’d like to acknowledge that. You’ve been delaying gratification; go out and do something nice. But don’t blow it all one night.

You also need to understand that, sure, your company went public, but you can’t sell any of this stock tomorrow, so you don’t want to put yourself at risk to commit to a lot of obligations, in the event that the stock plunges in value.

I’ve seen folks who, before the IPO, gifted significant amounts of stock to family members, and then 2000 happened, and they basically had gifted away all the value that they were going to receive.

Risk planning is the most relevant and prudent way of building a game plan. You have to understand risk early, set up a plan, and then follow through on it, tweaking it as life or career changes take hold.

We’ve seen other individuals who get to the liquidity event and really haven’t dealt with any of that planning. I recall a founder who came to us the week before he was getting married, and said, “I know I need the estate plan you told me about, but actually I failed to tell you that we’re getting married, and I’d like to have her sign a prenup. Can I get one drawn this week?”

Jeff: I’ve saved clients hundreds of thousands and even millions of dollars upon exits, just by doing some fundamental planning prior to an event.

Among the most relevant aspects of planning, even for a founder who’s laden with founder shares, is how they do the 83(b) elections (the official filing to exercise stock options) on their ISOs, and how they take into account their ordinary income and alternative minimum tax (AMT) situation alongside the calendar year, to optimize the amount of option exercise year over year over year.

There are decision points on a continual basis, say, over a two- or three-year period, where you can do a better job of avoiding tax, and also planning for your own personal liquidity.

How do you know if your plan isn’t working?

Andy: You’d look at some traditional things like how the market investments work against the benchmarks. Are you getting the cash flow you need to have the lifestyle that you really want? Are you able to take on the opportunities that present themselves in the market when you can get in?

Frankly, it takes a conversation with a good adviser, decision-making with that adviser, and then a commitment to the plan.

Say I just got my exit. How much money can I spend right now?

Jeff: There are two ways to address this question.

First, have a plan, and make sure that there’s been some assessment of taxes and how the assets are located on your balance sheet. Are there other issues at play, like options you can exercise that weren’t founder grants?

Second, be very clear and serious about what your lifestyle is. Most of the founders who get a lump of money – that’s extra. They don’t guide it right into the public stock market. It’s a good thing to get diversification and the guidance of a financial plan, and obviously, SVB can help with that.

It’s also important to know whether you need to budget a little bit for the next company you’re founding, or some angel investments or other co-investments you might want to make with your buddies.

Family, obviously, is also an important consideration for most folks we encounter.

So could I go buy myself a house?

Andy: The answer is if it’s prudent, and you qualify, absolutely, you should. That’s preferable to having a big old savings balance in a bank account.

Jeff: If you’re not sure, we can help you understand so you can be confident about these things. We do have clients that have come to us and said, “How much can I spend?” It’s more money than they had before, and they don’t know how to budget, and so they’re looking for help on learning how to budget.

Andy: Many of the things we talk about can seem a bit boring. But we try to have a lot of empathy. You have to in order to understand a client’s needs.

What parting advice would you offer to founders and executives of high growth startups?

Andy: Get the right team in place. When we ask the founder or executive how they have, to date or plan to, address their financial planning we often find that nothing has been done. Or very little has been done because they’ve been trying to do everything themselves. Quite understandably, they’ve been laser-focused on the business.

In their defense, it’s unrealistic to think that someone without any formal training in planning can really grasp it all themselves. They need someone to walk them through defining their goals and the right questions they should be asking themselves. They need advisers they can trust —wealth adviser, an accountant, a lawyer, a private banker, and an insurance specialist. There are a lot of pieces to arrange. The more assets there are, or will come in the future, the more complicated it is.

Jeff: At the risk of sounding like a commercial, for over three decades the bank has been exclusively serving those who build technology start-ups. We know the unique world they operate in. We know how they think. We know their lingua franca.

Therefore, we understand that we’re talking about hyper-confident people who are very certain about how to build these businesses we all admire. They’re fantastic at constructing a company balance sheet. But they’re not so confident and strategic in constructing a personal balance sheet. Entrusting someone, other than themselves, to develop a financial plan can feel more than a bit vulnerable to them.

But a founder should think about it the same way when they hire outstanding VPs to own the different functions of the company. They empower those executives and provide them with resources to accelerate their function and, subsequently, the company balance sheet. The only difference is that here we’re talking about their household, their family. It’s quite important.