Trending

Stock Options and Other Equity Compensation Strategies

/in Equity & Compensation/by Benjamin - WonderlyShare this entry

A Legal Guide to Secondaries

What Startups Need to Know About Employee Tender Offers

For private companies, deciding whether and how employees may sell shares can be tricky. On one hand, companies want to reward those whose efforts helped put a startup on the path to success. But the sales also have the potential to create a variety of headaches if not done thoughtfully—and potentially leave a company open to liability.

Craig Jacoby, a partner at Cooley LLP, has helped hundreds of startups with these secondary financings. We recently spoke to him about how companies should balance controlling their capitalization tables with providing liquidity opportunities to employees, and how to best manage some of the risk involved.

Here are edited excerpts of our conversation:

What do you emphasize when you talk to companies about employees selling shares?

Making it possible for employees to sell shares without restrictions isn’t an option we advise. It can serve as a distraction: What if all of your employees start keeping daily tabs on the current price per share of their stock? What if they start asking for company information that it doesn’t want to provide and potentially feed to prospective buyers? What if they sell to competitors?

It can also create some unwanted chaos. It can affect the company’s options pricing, it can affect who’s on the cap table, and it can lead to uneven pricing as each individual negotiates separately with what are typically sophisticated financial buyers. Companies are justifiably uncomfortable with all of those things.

So when we talk to companies, we talk about the benefits of broader board control over share transfers.

Historically, the primary protection that companies used to maintain some control over employee share sales has been a right-of-first-refusal (aka, ROFR, pronounced “rofer”) so that the company has the right to step in to repurchase the common shares at a price negotiated by the employee with a third party. This is fine when it’s the occasional individual employee considering a sale.

However, when there’s a really high level of demand for common shares, and a lot of employees willing to sell those shares, a company can’t keep exercising its ROFR. That would just drain cash that’s otherwise earmarked for growth initiatives.

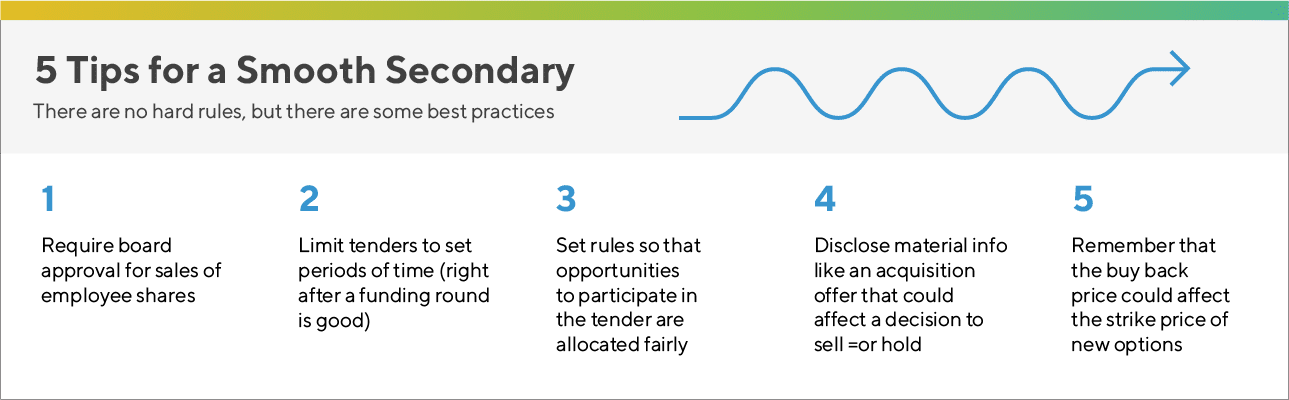

We often advise companies to put in much broader restrictions on the transfer of shares, and indeed this is much more common now. The most notable is that many companies now require board approval for almost any sales of common shares, and that would include transactions like loans secured by the shares and the sale of a call option, future contract or other derivative security based on the underlying shares. That means you can ask the board, but in general, the board just says “no.”

Where does that leave employees who want or need to get some liquidity?

The quid pro quo, in my mind, of companies clamping down on employees selling shares, is figuring out ways to create occasional liquidity opportunities.

In general, I find that companies are really receptive to the idea of providing liquidity opportunities for their employees that are handled in a fair way.

But overseeing that process takes a lot of work. There are transaction expenses and disclosure materials to put together—it’s a real effort by companies to manage a broad, inclusive program that makes liquidity available to people.

So companies prefer limiting those sales opportunities and organizing them as one burst of activity where you’re providing information to people, you’re doing it fairly and you’re making sure that your different shareholders get equal opportunity to participate.

That’s why you see bigger or more valuable private companies organize a tender offer in connection with, or right after, a large funding round. They do it fairly, when there has been a recent determination on price, and where they set the rules so that potential sellers are not pitted against one another in negotiating price and quantities with the potential buyer.

When it comes to a tender offer, the board has a lot more information than the employees do. Is that a potentially thorny legal situation?

In the scenario I just described, the company is basically setting a price and allowing people to participate or not. And yeah, there’s tremendous information asymmetry. In those deals, it’s important for a company to be really, really clear about what it knows that could raise or lower the share value in any material way.

If a company knows that it’s in discussions for an acquisition deal and at the same time it’s offering to repurchase employee shares without disclosing that, then depending on the acquisition price, that may create a huge problem.

Who buys the shares and sets the price in the tender offer also matters in these situations. If the buyer is the company or a current investor who has access to inside information, that’s different than if the tender offer is organized by an outside group that doesn’t have inside information access beyond what’s in the disclosure circulated to all of the potential sellers.

Are revenue growth or financial projections the sorts of things that you would advise companies to disclose in this type of situation?

Projections are a really hard one. I work with lots of companies that miss their projections dramatically, in one direction or the other. Public companies usually have vastly superior financial planning infrastructure and administrative capabilities and are often much better positioned than private companies to make more accurate predictions. It’s rarely appropriate for companies to include projections among the information disclosed to potential sellers.

In the case of a company-organized tender offers, what information do you advise disclosing to potential sellers?

The standard here is that any information that would reasonably be expected to affect someone’s decision to sell or hold the shares should be included. At either extreme, this is a simple analysis, with information about acquisition or financing offers and the loss of key executives or customers clearly requiring disclosure, while most normal day-to-day issues like individual customer wins and losses within expected ranges not requiring specific disclosure.

It’s always a good idea to include a set of detailed risk factors, as well as up-to-date financial statements. Balance is important. When a company is going public, the concerns are all on the side of ensuring that buyers have sufficient information, and so companies often include extensive disclosure of potential risks that have only a hypothetical chance of affecting the business, but in a company-organized tender, the complaints could come either from people who argue that with better disclosure they would not have sold or that with better disclosure they would not have held, so companies have to take both sides into account when preparing disclosures.

What other pitfalls should companies be mindful of?

Sometimes a company repurchase comes in the context of raising a preferred round of funding from new outside investors and using some of the proceeds of that financing to repurchase common stock from employees. Often, the price at which the company repurchases the common stock is somewhere between 65% and 100% of the price paid by the investors for preferred stock in the financing. We usually see the repurchase price for the common stock being at least a little lower than the price paid by investors for their preferred stock since the preferred stock almost always comes with additional voting and economic rights not enjoyed by the common stock.

Furthermore, if the company is saying “I’m willing to repurchase common stock at this price,” when it comes time to issue new stock option grants it’s hard for the company to establish an option strike price lower than the price it just paid for common stock. That can become a really meaningful constraint for the company in the aftermath of the tender offer.

Related Blog Posts

The State of Venture Debt

The 409a Valuation Process