Trending

Stock Options and Other Equity Compensation Strategies

/in Equity & Compensation/by Benjamin - WonderlyShare this entry

Tick Tock, the 10-year Expiration of Incentive Stock Options (ISOs)

Lynda Galligan & Anthony McCusker, Goodwin

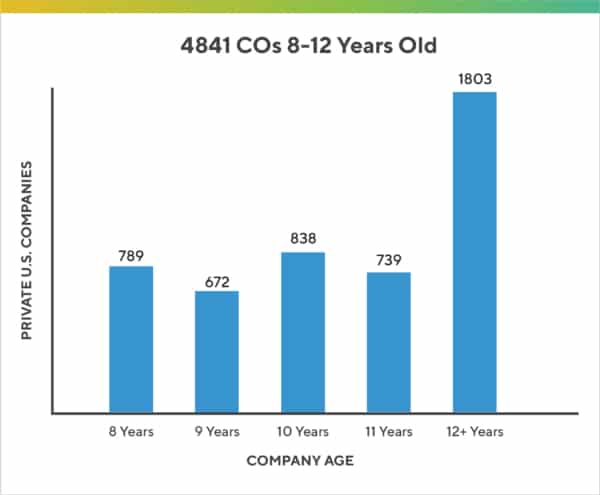

Mandated by US tax rules, unexercised employee stock options expire 10 years from date of grant and are absorbed back into the company. Historically, this was never a problem because the incentive stock model familiar to everyone was designed when companies aimed to go public as soon as they viably could. Now that top companies are staying private longer they’re being forced to rethink how they manage employee incentive stock programs.

We spoke with Lynda Galligan, a partner at Goodwin who specializes in compensation and benefits issues, and Anthony McCusker, chair of Goodwin’s Technology Companies Practice, about the challenges the 10-year lifespan for options creates for companies in this new environment and steps they can take to help their most valued employees exercise their stock options.

Edited Excerpts:

Source: Crunchbase; Founders Circle Research

How does the 10-year expiration of stock options become a real issue for companies?

If companies want to grant what we call a tax-qualified option, or an incentive stock option (ISO), they have to comply with a number of rules. One is that the options can’t have more than a 10-year life. If an employee reaches the 10-year expiration date, and they have yet to exercise their vested stock options, those options expire and get absorbed back into the company.

And a company can’t just extend that period for another 10 years without resetting the exercise price to the current 409A per share value, which is an unattractive alternative in most cases.

In our practice, the issue of employees reaching the 10-year expiration on their stock options comes up several times a year. And I would imagine that it’s only going to increase in frequency as many of the most successful companies elect to stay private longer.

Can an employee simply exercise their vested options before the expiration? And if so, when?

Exercising the options isn’t typically a problem since the exercise cost could be in the hundreds of dollars if the exercise price is pennies per share. It’s really about funding the tax bill, especially when you exercise options that are significantly in the money. Upon exercise, the tax bill is assessed at the fair market value of the stock, or the 409A valuation, minus the strike price based on the applicable tax rate (alternative minimum tax rate for ISOs or ordinary income tax rate for NSOs). Even though someone could easily write out a check for a few hundred dollars to exercise their stock options, they also need to come up with the money to pay the accompanying taxes that could be in the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars.

So what are a company’s choices?

There are several.

One is to do nothing. The employee had 10 years to exercise their options. If the company wanted to take a hard line, it could say, “Sorry. Your options expired.” As a practical matter, that’s not a good solution, because the options are likely held by someone who is valuable to the company. So, we recommend against this approach.

Second, if the first grant of stock options expire, the company could grant new stock options. But those new options must be reset at an exercise price that’s equal to current market value. Section 409A of the IRS tax code says the exercise price of a new option, on the grant date, has to be no less than the fair-market value of the company stock (the value established by a 409A audit firm). While this approach certainly attempts to provide the employee with a wealth creation opportunity, it usually comes at a significantly higher cost because the original grant was likely a pennies/share price and the new grant is often a many dollars/share price. While new options can theoretically be structured to have a discounted exercise price while not running afoul of the Section 409A rules, most companies find the required structuring to be impractical and therefore unworkable.

A variation on this approach is that the company could grant restricted stock units (RSUs) for an equivalent (or lesser) number of shares under the expired option. With an RSU, the employee eventually takes ownership of the stock at a future liquidity event, without having to pay the exercise cost. However, upon taking possession, he is still going to have the tax bill. Furthermore, companies and employees often have a hard time agreeing on the terms of the conversion, namely around what is the value of a share of stock and how many ISOs equal how many RSUs.

Third, a company may want to help the employee to exercise their stock options by facilitating a cashless exercise via a company buy-back. Employees sell some of their to-be exercised shares to cover the exercise cost and to pay their taxes. But the company is basically purchasing shares at that point, so it’s real money coming out of the company’s balance sheet to fund the employee’s tax bill.

A variation on this approach is that the company could allow option exercises using a promissory note. The company would loan the employee the money for the exercise and tax costs. But again, the company would have to use its balance sheet for the taxes. It’s not a cash-free transaction.

And there are some other restrictions around promissory notes. These kinds of notes are typically only provided to an officer or director of the company or sometimes to a small handful of employees who have a common circumstance. In any case, a company can’t have any outstanding loans to officers or directors as it becomes a public company. Once the company proceeds towards its public offering, it’d have to take care of that note before filing an S-1. There are also limits on the number of outstanding loans a company can carry.

Lastly, a company could give bonuses to employees to cover the exercise and tax costs. One thing to note with bonuses is that a company can’t require that they be used to exercise options. If the employee would rather use those funds for something else, that has to be allowed. If the bonus can only be used to exercise the option, then that raises a 409A problem. And, obviously, the company may want (or have) to use its cash for purposes other than employee bonuses.

Does the new tax law change my strategy?

There is some good recent news: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 could potentially hold some upside when shares become liquid, by deferring taxation for up to five years until liquidity is achieved in limited cases. However, this new law includes several onerous requirements that are likely to significantly limit its appeal. To see if that applies to you, have your financial planner look closely at the Tax Deferral for Option Exercise – New Section 83(i) Election of the act.

It seems like there are ample options to pursue.

In the end, all of these solutions have complications. We recently assisted a later stage startup to explore a number of these options for one of its executives. They thought about providing a loan to the executive. But the company was beginning to consider a future public offering and didn’t want to deal with getting the loan off the books before the IPO. Then the company offered to consider granting RSUs once the ISOs expired. But what seemed like a straightforward exchange based upon the total value of the ISO became a lengthy unresolved negotiation—what was the true current value of the stock, was the 409A a fair and accurate representation of the value, how many shares of RSUs did it equate to, how to minimize the tax obligation? Ultimately, the company found an investor to conduct a secondary and buy the executive’s vested shares to fund the exercise and tax costs.

When does your firm tend to see secondaries being conducted?

The options we’ve discussed so far are only for a small handful of people. And solving for the needs of a few does not end the problem as typically an ever increasing number of employees will be approaching the 10-year expiration date. As the numbers increase, the math makes it not feasible or desirable for a company to use some of its cash to help employees. Dealing with the problem in a one-off fashion doesn’t address broader based issues that will arise.

That’s why a number of the companies we work with, where more than a handful of employees are approaching options expiration, organize an employee-wide tender offer as one path forward to solving that issue. Typically that’s through an outside investor, either in connection with a financing round or in between, to take care of options expirations, as well as give employees some liquidity. It gives the employee a path to pay for the exercise and tax costs.

What about the 83(b) election, why doesn’t a company promote the use of that simple tool early on as opposed to relying on the complexity of a secondary as it approaches 10 years?

When you’re a very early employee, with restricted stock or incentive stock options, where your strike price is at 2 cents per share, it’s kind of a no-brainer that an employee should use the 83(b), so long as it’s executed in the required timeframe, as it would result in a de minimis exercise and tax cost.

But it gets trickier as the company moves along in value. Once the stock value has appreciated, exercising and using the 83(b) election could equate to a meaningful check from the employee. The company also needs to be careful to not over-promote the prospects and the value of the company such that it might drive employees to exercise their shares. If, in the future, the company does not succeed they could possibly be exposed to a liability claim. They need to let the employee come to their own conclusions about the company’s prospects and the manner with which they choose to exercise their shares.

It really puts companies in a quandary. Most CEOs care about and want to help and want their employees to stay motivated to build the business. They gladly provide the incentive stock in the first place. But then they have to exercise an abundance of caution never to be seen as giving any kind of financial, tax or legal advice nor to be seen as promoting the stock.

If you were advising a younger startup today, what takeaways would you give them?

For the CEO, CFO and BOD, the 10-year expiration issue isn’t a one-off. It’s the beginning of a wave, and they should be strategic about solving it and have a plan for when the need for employee liquidity arises and, inevitably, increases.

For the company, they ought to work with objective third parties to educate their employees about their exercise and liquidity options. It’s not that much different than educating employees about the benefits of 401K savings and the options available to them for doing so.

For the employee, they should understand the risks and rewards of exercising their vested stock options early and ongoing. Again, it’s conceptually the same as when they have a little bit of each paycheck diverted to their 401K program where value is slowly built over time. The obvious risk is that the employee might be cash out of pocket for stock that could be worthless in the future. However, the fundamental reward is a greater wealth creation moment in the future because far lower taxes were paid along the way.

Related Blog Posts

The State of Venture Debt

The 409a Valuation Process